Nationality

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

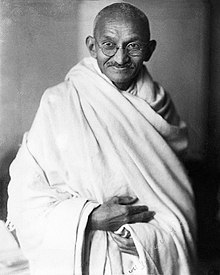

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (/ˈɡɑːndi, ˈɡændi/;[3] GAHN-dee; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was an Indian lawyer,[4] anti-colonial nationalist[5] and political ethicist[6] who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule,[7] and to later inspire movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā (Sanskrit: "great-souled", "venerable"), first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa, is now used throughout the world.[8][9]

Born and raised in a Hindu family in coastal Gujarat, Gandhi trained in the law at the Inner Temple, London, and was called to the bar at age 22 in June 1891. After two uncertain years in India, where he was unable to start a successful law practice, he moved to South Africa in 1893 to represent an Indian merchant in a lawsuit. He went on to live in South Africa for 21 years. It was here that Gandhi raised a family and first employed nonviolent resistance in a campaign for civil rights. In 1915, aged 45, he returned to India and soon set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against excessive land-tax and discrimination.

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and, above all, achieving swaraj or self-rule. Gandhi adopted the short dhoti woven with hand-spun yarn as a mark of identification with India's rural poor. He began to live in a self-sufficient residential community, to eat simple food, and undertake long fasts as a means of both introspection and political protest. Bringing anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930 and in calling for the British to quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned many times and for many years in both South Africa and India.

Gandhi's vision of an independent India based on religious pluralism was challenged in the early 1940s by a Muslim nationalism which demanded a separate homeland for Muslims within British India.[10] In August 1947, Britain granted independence, but the British Indian Empire[10] was partitioned into two dominions, a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan.[11] As many displaced Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs made their way to their new lands, religious violence broke out, especially in the Punjab and Bengal. Abstaining from the official celebration of independence, Gandhi visited the affected areas, attempting to alleviate distress. In the months following, he undertook several hunger strikes to stop the religious violence. The last of these, begun in Delhi on 12 January 1948 when he was 78,[12] also had the indirect goal of pressuring India to pay out some cash assets owed to Pakistan.[12] Although the Government of India relented, as did the religious rioters, the belief that Gandhi had been too resolute in his defence of both Pakistan and Indian Muslims, especially those besieged in Delhi, spread among some Hindus in India.[13][12] Among these was Nathuram Godse, a militant Hindu nationalist from western India, who assassinated Gandhi by firing three bullets into his chest at an interfaith prayer meeting in Delhi on 30 January 1948.[14]

Biography

Early life and background

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi[20] was born on 2 October 1869[21] into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family[22][23] in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar state.[24][25] His family originated from the then village of Kutiana in what was then Junagadh State.[26]

Although he only had an elementary education and had previously been a clerk in the state administration, Karamchand proved a capable chief minister.[27] During his tenure, Karamchand married four times. His first two wives died young, after each had given birth to a daughter, and his third marriage was childless. In 1857, Karamchand sought his third wife's permission to remarry; that year, he married Putlibai (1844–1891), who also came from Junagadh,[27] and was from a Pranami Vaishnava family.[28] Karamchand and Putlibai had three children over the ensuing decade: a son, Laxmidas (c. 1860–1914); a daughter, Raliatbehn (1862–1960); and another son, Karsandas (c. 1866–1913).[29][30]

On 2 October 1869, Putlibai gave birth to her last child, Mohandas, in a dark, windowless ground-floor room of the Gandhi family residence in Porbandar city. As a child, Gandhi was described by his sister Raliat as "restless as mercury, either playing or roaming about. One of his favourite pastimes was twisting dogs' ears."[31] The Indian classics, especially the stories of Shravana and king Harishchandra, had a great impact on Gandhi in his childhood. In his autobiography, he admits that they left an indelible impression on his mind. He writes: "It haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number." Gandhi's early self-identification with truth and love as supreme values is traceable to these epic characters.[32][33]

The family's religious background was eclectic. Gandhi's father Karamchand was Hindu and his mother Putlibai was from a Pranami Vaishnava Hindu family.[34][35] Gandhi's father was of Modh Baniya caste in the varna of Vaishya.[36] His mother came from the medieval Krishna bhakti-based Pranami tradition, whose religious texts include the Bhagavad Gita, the Bhagavata Purana, and a collection of 14 texts with teachings that the tradition believes to include the essence of the Vedas, the Quran and the Bible.[35][37] Gandhi was deeply influenced by his mother, an extremely pious lady who "would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers... she would take the hardest vows and keep them without flinching. To keep two or three consecutive fasts was nothing to her."[38]

In 1874, Gandhi's father Karamchand left Porbandar for the smaller state of Rajkot, where he became a counsellor to its ruler, the Thakur Sahib; though Rajkot was a less prestigious state than Porbandar, the British regional political agency was located there, which gave the state's diwan a measure of security.[39] In 1876, Karamchand became diwan of Rajkot and was succeeded as diwan of Porbandar by his brother Tulsidas. His family then rejoined him in Rajkot.[40]

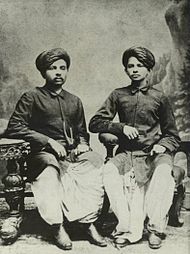

Gandhi (right) with his eldest brother Laxmidas in 1886[41]

At age 9, Gandhi entered the local school in Rajkot, near his home. There he studied the rudiments of arithmetic, history, the Gujarati language and geography.[40] At age 11, he joined the High School in Rajkot, Alfred High School.[42] He was an average student, won some prizes, but was a shy and tongue tied student, with no interest in games; his only companions were books and school lessons.[43]

In May 1883, the 13-year-old Mohandas was married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Makhanji Kapadia (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba", and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged marriage, according to the custom of the region at that time.[44] In the process, he lost a year at school but was later allowed to make up by accelerating his studies.[45] His wedding was a joint event, where his brother and cousin were also married. Recalling the day of their marriage, he once said, "As we didn't know much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives." As was prevailing tradition, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents' house, and away from her husband.[46]

Writing many years later, Mohandas described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride, "even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me." He later recalled feeling jealous and possessive of her, such as when she would visit a temple with her girlfriends, and being sexually lustful in his feelings for her.[47]

In late 1885, Gandhi's father Karamchand died.[48] Gandhi, then 16 years old, and his wife of age 17 had their first baby, who survived only a few days. The two deaths anguished Gandhi.[48] The Gandhi couple had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas, born in 1900.[44]

In November 1887, the 18-year-old Gandhi graduated from high school in Ahmedabad.[49] In January 1888, he enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar State, then the sole degree-granting institution of higher education in the region. But he dropped out and returned to his family in Porbandar.[50]

Three years in London

Student of law

Commemorative plaque at 20 Baron's Court Road, Barons Court, London

Gandhi had dropped out of the cheapest college he could afford in Bombay.[51] Mavji Dave Joshiji, a Brahmin priest and family friend, advised Gandhi and his family that he should consider law studies in London.[52] In July 1888, his wife Kasturba gave birth to their first surviving son, Harilal.[53] His mother was not comfortable about Gandhi leaving his wife and family, and going so far from home. Gandhi's uncle Tulsidas also tried to dissuade his nephew. Gandhi wanted to go. To persuade his wife and mother, Gandhi made a vow in front of his mother that he would abstain from meat, alcohol and women. Gandhi's brother Laxmidas, who was already a lawyer, cheered Gandhi's London studies plan and offered to support him. Putlibai gave Gandhi her permission and blessing.[50][54]

Gandhi in London as a law student

On 10 August 1888, Gandhi aged 18, left Porbandar for Mumbai, then known as Bombay. Upon arrival, he stayed with the local Modh Bania community whose elders warned him that England would tempt him to compromise his religion, and eat and drink in Western ways. Despite Gandhi informing them of his promise to his mother and her blessings, he was excommunicated from his caste. Gandhi ignored this, and on 4 September, he sailed from Bombay to London, with his brother seeing him off.[53][55] Gandhi attended University College, London, a constituent college of the University of London.

At UCL, he studied law and jurisprudence and was invited to enrol at Inner Temple with the intention of becoming a barrister. His childhood shyness and self-withdrawal had continued through his teens. He retained these traits when he arrived in London, but joined a public speaking practice group and overcame his shyness sufficiently to practise law.[56]

He demonstrated a keen interest in the welfare of London’s impoverished dockland communities. In 1889, a bitter trade dispute broke out in London, with dockers striking for better pay and conditions, and seamen, shipbuilders, factory girls and other joining the strike in solidarity. The strikers were successful, in part due to the mediation of Cardinal Manning, leading Gandhi and an Indian friend to make a point of visiting the cardinal and thanking him for his work.[57]

Vegetarianism and committee work

Gandhi's time in London was influenced by the vow he had made to his mother. He tried to adopt "English" customs, including taking dancing lessons. However, he did not appreciate the bland vegetarian food offered by his landlady and was frequently hungry until he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, he joined the London Vegetarian Society and was elected to its executive committee[58] under the aegis of its president and benefactor Arnold Hills. An achievement while on the committee was the establishment of a Bayswater chapter.[59] Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original.[58]

Gandhi had a friendly and productive relationship with Hills, but the two men took a different view on the continued LVS membership of fellow committee member Thomas Allinson. Their disagreement is the first known example of Gandhi challenging authority, despite his shyness and temperamental disinclination towards confrontation.

Allinson had been promoting newly available birth control methods, but Hills disapproved of these, believing they undermined public morality. He believed vegetarianism to be a moral movement and that Allinson should therefore no longer remain a member of the LVS. Gandhi shared Hills' views on the dangers of birth control, but defended Allinson's right to differ.[60] It would have been hard for Gandhi to challenge Hills; Hills was 12 years his senior and unlike Gandhi, highly eloquent. He bankrolled the LVS and was a captain of industry with his Thames Ironworks company employing more than 6,000 people in the East End of London. He was also a highly accomplished sportsman who later founded the football club West Ham United. In his 1927 An Autobiography, Vol. I, Gandhi wrote:

The question deeply interested me...I had a high regard for Mr. Hills and his generosity. But I thought it was quite improper to exclude a man from a vegetarian society simply because he refused to regard puritan morals as one of the objects of the society[60]

A motion to remove Allinson was raised, and was debated and voted on by the committee. Gandhi's shyness was an obstacle to his defence of Allinson at the committee meeting. He wrote his views down on paper but shyness prevented him from reading out his arguments, so Hills, the President, asked another committee member to read them out for him. Although some other members of the committee agreed with Gandhi, the vote was lost and Allinson excluded. There were no hard feelings, with Hills proposing the toast at the LVS farewell dinner in honour of Gandhi's return to India.[61]

Books

- Ahmed, Talat (2018). Mohandas Gandhi: Experiments in Civil Disobedience. ISBN 0-7453-3429-6.

- Barr, F. Mary (1956). Bapu: Conversations and Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi (2nd ed.). Bombay: International Book House. OCLC 8372568. (see book article)

- Bondurant, Joan Valérie (1971). Conquest of Violence: the Gandhian philosophy of conflict. University of California Press.

- Brown, Judith M. (2004). "Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand [Mahatma Gandhi] (1869–1948)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing]

- Brown, Judith M., and Anthony Parel, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Gandhi (2012); 14 essays by scholars

- Brown, Judith Margaret (1991). Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05125-4.

- Chadha, Yogesh (1997). Gandhi: a life. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-24378-6.

- Dwivedi, Divya; Mohan, Shaj; Nancy, Jean-Luc (2019). Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theological Anti-politics. Bloomsbury Academic, UK. ISBN 978-1-4742-2173-3.

- Louis Fischer. The Life of Mahatma Gandhi (1957) online

- Easwaran, Eknath (2011). Gandhi the Man: How One Man Changed Himself to Change the World. Nilgiri Press. ISBN 978-1-58638-055-7.

- Hook, Sue Vander (2010). Mahatma Gandhi: Proponent of Peace. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-61758-813-6.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (1990), Patel, A Life, Navajivan Pub. House

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2006). Gandhi: The Man, His People, and the Empire. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25570-8.

- Gangrade, K.D. (2004). "Role of Shanti Sainiks in the Global Race for Armaments". Moral Lessons From Gandhi's Autobiography And Other Essays. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-8069-084-6.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2013). Gandhi Before India. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-385-53230-3.

- Hardiman, David (2003). Gandhi in His Time and Ours: the global legacy of his ideas. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-711-8.

- Hatt, Christine (2002). Mahatma Gandhi. Evans Brothers. ISBN 978-0-237-52308-4.

- Herman, Arthur (2008). Gandhi and Churchill: the epic rivalry that destroyed an empire and forged our age. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-553-80463-8.

- Jai, Janak Raj (1996). Commissions and Omissions by Indian Prime Ministers: 1947–1980. Regency Publications. ISBN 978-81-86030-23-3.

- Johnson, Richard L. (2006). Gandhi's Experiments with Truth: Essential Writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1143-7.

- Jones, Constance & Ryan, James D. (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9.

- Majmudar, Uma (2005). Gandhi's Pilgrimage of Faith: from darkness to light. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6405-2.

- Miller, Jake C. (2002). Prophets of a just society. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-068-5.

- Pāṇḍeya, Viśva Mohana (2003). Historiography of India's Partition: an analysis of imperialist writings. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0314-6.

- Pilisuk, Marc; Nagler, Michael N. (2011). Peace Movements Worldwide: Players and practices in resistance to war. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36482-2.

- Rühe, Peter (2004). Gandhi. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-4459-6.

- Schouten, Jan Peter (2008). Jesus as Guru: the image of Christ among Hindus and Christians in India. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2443-4.

- Sharp, Gene (1979). Gandhi as a Political Strategist: with essays on ethics and politics. P. Sargent Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87558-090-6.

- Shashi, S. S. (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- Sinha, Satya (2015). The Dialectic of God: The Theosophical Views Of Tagore and Gandhi. Partridge Publishing India. ISBN 978-1-4828-4748-2.

- Sofri, Gianni (1999). Gandhi and India: a century in focus. Windrush Press. ISBN 978-1-900624-12-1.

- Thacker, Dhirubhai (2006). ""Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand" (entry)". In Amaresh Datta (ed.). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume Two) (Devraj To Jyoti). Sahitya Akademi. p. 1345. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0.

- Todd, Anne M (2004). Mohandas Gandhi. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-7864-8.; short biography for children

- Wolpert, Stanley (2002). Gandhi's Passion: the life and legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972872-5.

Scholarly articles

- Danielson, Leilah C. "'In My Extremity I Turned to Gandhi': American Pacifists, Christianity, and Gandhian Nonviolence, 1915–1941". Church History 72.2 (2003): 361–388.

- Du Toit, Brian M. "The Mahatma Gandhi and South Africa." Journal of Modern African Studies 34#4 (1996): 643–660. JSTOR 161593.

- Gokhale, B. G. "Gandhi and the British Empire," History Today (Nov 1969), 19#11 pp 744–751 online.

- Juergensmeyer, Mark. "The Gandhi Revival – A Review Article." The Journal of Asian Studies 43#2 (Feb. 1984), pp. 293–298. JSTOR 2055315

- Kishwar, Madhu. "Gandhi on Women." Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 41 (1985): 1753–758. JSTOR 4374920.

- Murthy, C. S. H. N., Oinam Bedajit Meitei, and Dapkupar Tariang. "The Tale Of Gandhi Through The Lens: An Inter-Textual Analytical Study Of Three Major Films-Gandhi, The Making Of The Mahatma, And Gandhi, My Father." CINEJ Cinema Journal 2.2 (2013): 4–37. online

- Power, Paul F. "Toward a Revaluation of Gandhi's Political Thought." Western Political Quarterly 16.1 (1963): 99–108 excerpt.

- Rudolph, Lloyd I. "Gandhi in the Mind of America." Economic and Political Weekly 45, no. 47 (2010): 23–26. JSTOR 25764146.

Explanatory notes

- ^ [106][110][111][112]

- ^ The earliest record of usage, however, is in a private letter from Pranjivan Mehta to Gopal Krishna Gokhale dated 1909.[399][400]